When someone enters a guilty plea, a no contest plea, or is found guilty at trial, they have been convicted of a crime. After a conviction, that person appears at a sentencing hearing during which a judge explains what the punishment will be. Normally, sentencing results in a judge placing the convicted person on probation, or sending them to jail or prison (in other words: incarceration)1. But how does a judge determine if the convicted person should get probation versus sending them to jail or prison? And if punishment is left totally up to the judge, wouldn’t that mean that someone in front of Judge A could get probation, while someone in front of Judge B gets life in prison?

These questions resulted in a system called the sentencing guidelines. The sentencing guidelines are a set of instructions for judges that were enacted into law by the United States and Michigan. The guidelines provide judges with a fixed range from which they choose how long to begin the punishment for a person convicted of a felony2. If a judge goes above or below that fixed range, they must provide an explanation or they risk the punishment being overturned by an appeals court. It is important to note that the maximum amount of time a convicted person can be incarcerated is set by law, so the sentencing guidelines only provide judges with a range for the minimum amount of time the convicted person will be incarcerated.

In Michigan, sentencing guidelines use two prongs to determine what type of punishment a convicted person should receive. The first prong is the convicted person’s criminal history. Michigan calls this prong the Prior Record Variables, or PRVs. To determine an accused person’s PRV score, the sentencing guidelines look at factors including how many prior convictions a person has, how many crimes they allegedly committed at one time, and whether they were on probation or parole at the time they allegedly committed the new offense. The higher the PRV score, the harsher the punishment will be.

The second prong does not look at an individual’s criminal history3, but instead looks at how severe this particular alleged criminal activity was. Michigan calls this factor the Offense Variables, or OVs. To determine an accused person’s OV score, the sentencing guidelines look at factors including whether the accused person had a weapon during the alleged crime, whether the accused person hurt anyone during the alleged crime, and whether the accused person interfered with the police’s efforts to investigate the alleged crime. Like with PRVs, the higher the OV score, the harsher the punishment will be.

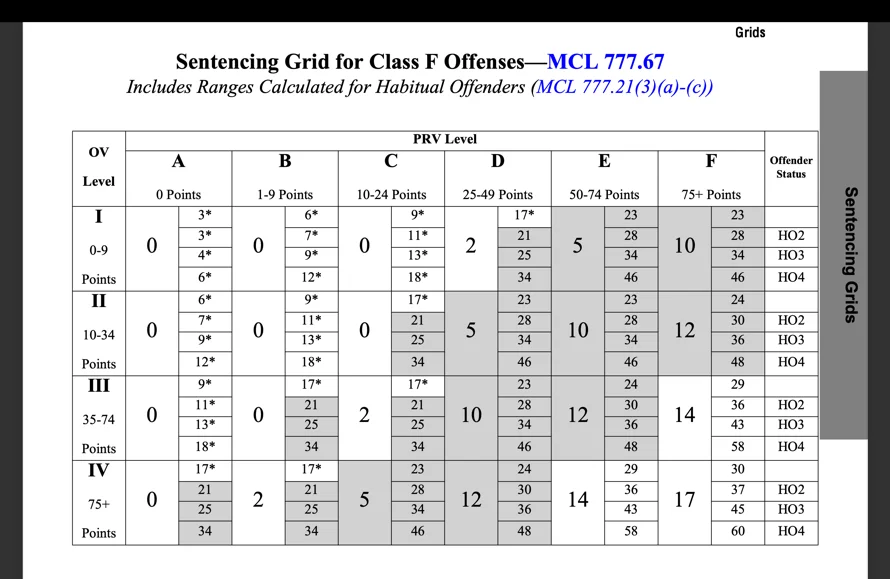

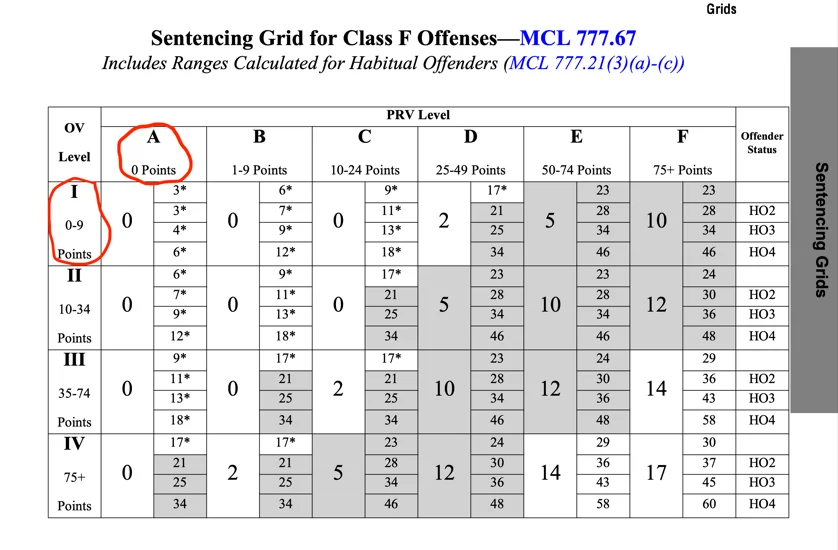

Once the lawyers determine an accused person’s PRV score and OV score, they look at a sentencing grid to find the intersection of those scores. Because the government considers some crimes to be more severe than others (murder is more severe than running from the police), different crimes correspond to different sentencing grids. The more severe the crime, the higher the grid used, and the harsher the punishment will be.

An Example of a Sentencing Grid

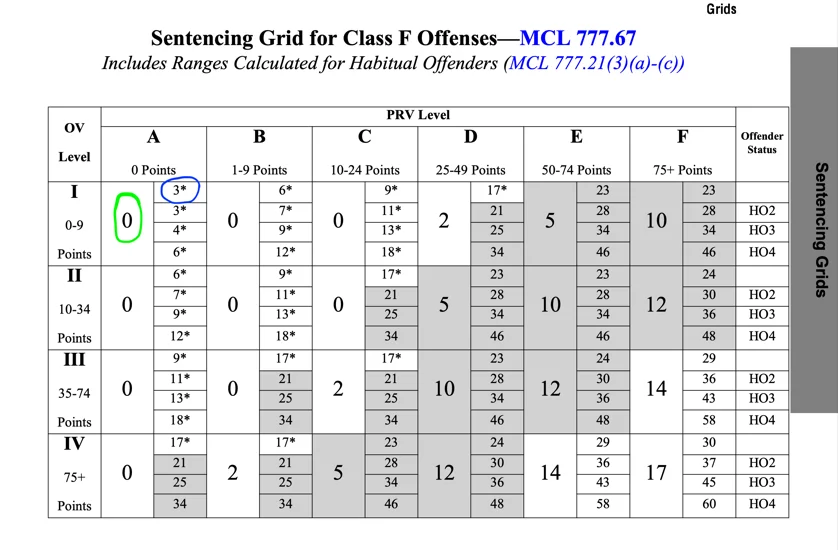

Let’s look at an example. Using the sentencing grid above, let’s say that an accused person’s PRV score is 0 points – meaning they have no criminal history whatsoever. Let’s also say that person’s OV score is 0 points – meaning the crime they are accused of was not particularly severe. On the grid above, that would place them in the A column and the I row.

The large number inside the A-I box (noted by the green circle) at that intersection represents the low end of the sentencing guideline range for this crime and this accused person. The small number inside the A-I box (noted by the blue circle) is the high end of the sentencing guideline range for this crime and this accused person.4

This means that the guideline range for this crime and this accused person is 0 to 3 months of incarceration. Since a judge who is following the guidelines will determine the minimum amount of time the convicted person will spend incarcerated, that means they get to choose anywhere between 0 and 3 months of incarceration. For example, again, we will say the judge chooses 2 months. Because the maximum amount of time the convicted person will spend in jail or prison is set by the law (for this example we will say 4 years), the convicted person in this example will spend anywhere between 2 months and 4 years incarcerated.

Knowing how the sentencing guidelines work is one of the most important skills a criminal lawyer must master. Not only do judges use the guidelines to make decisions on punishment, but prosecutors use the guidelines when determining how good of a plea offer to make before an accused person has even admitted guilt or had a trial. That means it is vital for your defense attorney to know not just how the guidelines work, but also what arguments to make to help shape your guidelines so they are more favorable to you and you get a lower sentence. KBW Criminal Law’s founding attorney, Kevin, has scored the sentencing guidelines for hundreds of cases and made countless arguments to change guideline scoring. If you are convicted of a crime, you want an expert in the guidelines like Kevin presenting every feasible argument to keep your punishment as low as possible.

- Check out the What to Expect page for more information on these possibilities. ↩︎

- Note that judges do not use the sentencing guidelines to make punishment decisions for persons convicted of traffic offenses and misdemeanors – only felonies. ↩︎

- (mostly) ↩︎

- You may notice that there are several other small numbers in the A-I box, but you can ignore them for the purposes of this teaching. ↩︎